150 YEARS AGO THIS WEEK (21st- 27th FEBRUARY 1872)

This week's stories include the deadly boiler explosion in a St Helens chemical works, the fire that raged all night in Sutton Heath, the black artists and serio-comics at the Theatre Royal, the 10-year-old Prescot girl who was sent to prison and the Pilkington apprentice who prosecuted his foreman for boxing his ears.

We begin with a meeting of the Crank Band of Hope during the evening of the 21st. The speaker was Rev. Miller from St Helens who gave a speech on the "power of evil habits" and expressed his hope that such temperance groups as Crank's would save thousands of young people "from the habits that now terribly enslaved so many of the old".

The Prescot Petty Sessions heard that a girl called Ann Giblin had stolen 6s 6d from the drawer of a beerhouse in Kemble Street in Prescot after ordering a pint of beer. The 10-year-old's father, John Giblin, said he could do no good with his child, having sent her to school – but instead she loitered about the streets. However, the 1871 census, taken 11 months earlier, has the girl listed as a labourer, along with her 12-year-old sister Mary. The siblings' younger brothers, though, are both marked as scholars.

If it had been the child’s first offence and there had been a suitable plea from the father, it is likely that the magistrates would have treated Ann more favourably. But once her Dad used the words "can do no good with him / her", long-term custody was the inevitable fate. So the girl from Bond Street in Prescot was sent to prison for a month and then onto a reformatory for five years.

This week's turns at the St Helens Theatre Royal Concert Hall were again centred on minstrel performances by black artists and the so-called serio-comics. Grotesque parodies of black life in America and dry humoured comedians were probably the two most popular forms of entertainment in the 1870s. The latter continues to this day with the Les Dawson / Jack Dee brand of comedy but thankfully the former in all its forms has long gone.

All but one of the five acts playing in the premises we know as the Citadel this week fitted into the serio-comic and black comic categories and were: Harry Dales ("The original “Lazy Sam”"); Miss Clara Robie ("Serio-comic and dancer"); Sam Redden ("Negro comedian"); Miss Julia Sutherland ("Excellent serio-comic, singer and dancer") and D’Osta and Little Ebor ("First-class gymnasts").

A review of Harry Dales' performance in London from June 1872 said: "Mr. Harry Dales supplies the “Ni**er” element. On the night of our visit he sang a somewhat dolorous [sad] medley concerning “Uncle Tom,” but we soon forgot this in his subsequent agility. Mr. Hales calls himself the original “Lazy Sam,” but his nimbleness of foot belies his title. A better performer on the bones we have never heard."

And an advert for Sam Redden in The Era trade newspaper in 1873 said: "The original and only Sam Redden, the Celebrated Negro Comedian, Stump Orator, Instrumentalist, Vocalist, and Eccentric Dancer, now on a successful tour through Wales, in his unique entertainment, entitled “Down South,” acknowledged by proprietors, public, and press to be the ne plus ultra of Negro Minstrelsy. “Causes screams of laughter without the slightest tinge of vulgarity”."

The St Helens Newspaper wrote on the 24th: "A conflagration of the most destructive character broke out at Eltonhead Farm, Sutton Heath, on Sunday night". It was another example of the difficulties incurred in the 1870s when a serious fire occurred in a rural area. No telephones to rapidly communicate news of the outbreak to a fire brigade and no motor vehicles or high quality roads to rapidly transport them to the blaze.

Then there was the issue of sourcing a water supply and efficiently playing it on the fire. No wonder the Newspaper wrote that it had been apparent from an early stage that the building was "doomed". The Lowe family ran Eltonhead Farm and a man who spotted the blaze in a large barn late at night dashed to the nearby home of Thomas Lowe to break the news. After releasing some cattle from the burning building, Lowe rode on horseback to Rainhill Lunatic Asylum – as it was then known.

Because of the time it took for town brigades to reach out of the way locations, some works and institutions kept their own engines. Rainhill asylum kept one and a small brigade of men. As they made their way to Eltonhead, Thomas Lowe rode on to Prescot to summon the town brigade. Once both units were in position, Dr Thomas Rogers took charge. The Newspaper credited his "energy and coolness" in localising the fire.

Dr Rogers was the superintendent in charge of Rainhill Asylum and clearly did a good job – although I think if my place was on fire, I would not expect a doctor in charge of a mental hospital to be commanding the fire brigade! The fire raged all night and an immense quantity of unthreshed wheat stored in the granary was destroyed and six heifers died. Then the fire began again in the afternoon. It was supposed that a labourer sleeping on the premises had caused it. The man had not been seen since and it was thought he might have been burned to death in the inferno.

However, that is not the end of this account. A letter was subsequently published in the Newspaper condemning the St Helens Borough Fire Brigade. It was claimed that they had been notified of the blaze both by telegram and special messenger (i.e. man on a horse) around midnight on the Sunday evening – but didn't show up until 4pm on the Monday afternoon! And then it was stated that they wanted a reassurance of their beer supply before setting to work. "“No beer no water” appeared to be the motto", claimed the correspondent.

The lengthy delay in the fire brigade’s arrival might have been connected with another emergency that had taken place ten hours earlier. The Sheffield Daily Telegraph described what had occurred: "On Sunday afternoon, at two o'clock, five boilers, filled with caustic soda, exploded at Messrs. Evans and McBryde's chemical works, Pocket Nook, near St. Helens, causing the loss of three lives and serious destruction of property.

"So great was the force of the explosion that half of one of the boilers was hurled a distance of 250 yards, and embedded several feet in the soil. Another great mass of iron was thrown on to the roof of glassworks, which it smashed in. The sheds under which the boilers stood were thrown into the air a great height, and were enveloped in a cloud of steam, which, with the terrific noise which accompanied the explosion, was seen and heard for miles round.

"Fortunately, it was Sunday, but few persons were at the works, except those engaged at the engine and boiler, and the loss of life has not been so great as the extent of the damage would lead one to suppose. A space of about 2,500 square yards, where the boilers and oxidisers stood, is a heap of ruins, and the roofs and windows in the neighbourhood have suffered considerably from the missiles which were thrown into the air by the explosion."

In fact four men were killed and eight injuried. The dead were William Marsh from Blackbrook; Michael Kelly of Greenbank; William Plumbley from Eccleston and James Lee. The St Helens Newspaper described the latter as "a black man of Pocket Nook" who lived in lodgings in David Street.

Several persons walking in the vicinity of the works were also badly scalded or otherwise hurt by boiling liquid falling upon them. Some were children playing in a field. The injured included a 7-year-old boy called Michael Gallagher ("badly scalded all over the body") and 9-year-old Francis Gallagher ("arm broken, large scalp wound, bruised"). Catherine Roberts of David Street in Pocket Nook was also severely scalded by the hot caustic landing on her while she'd been passing the works.

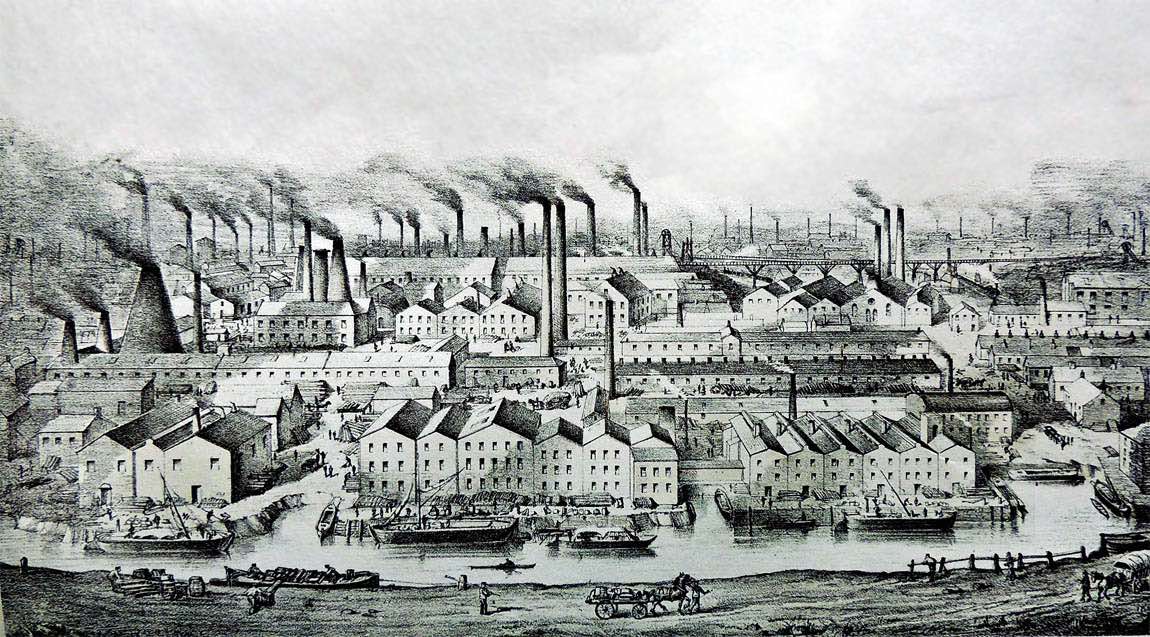

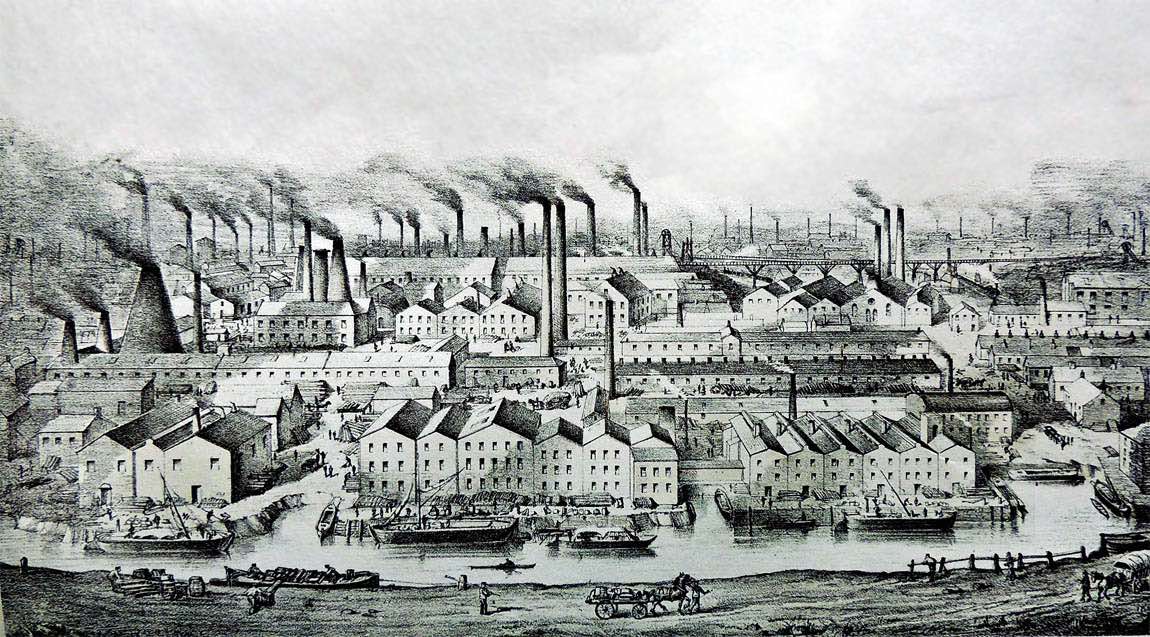

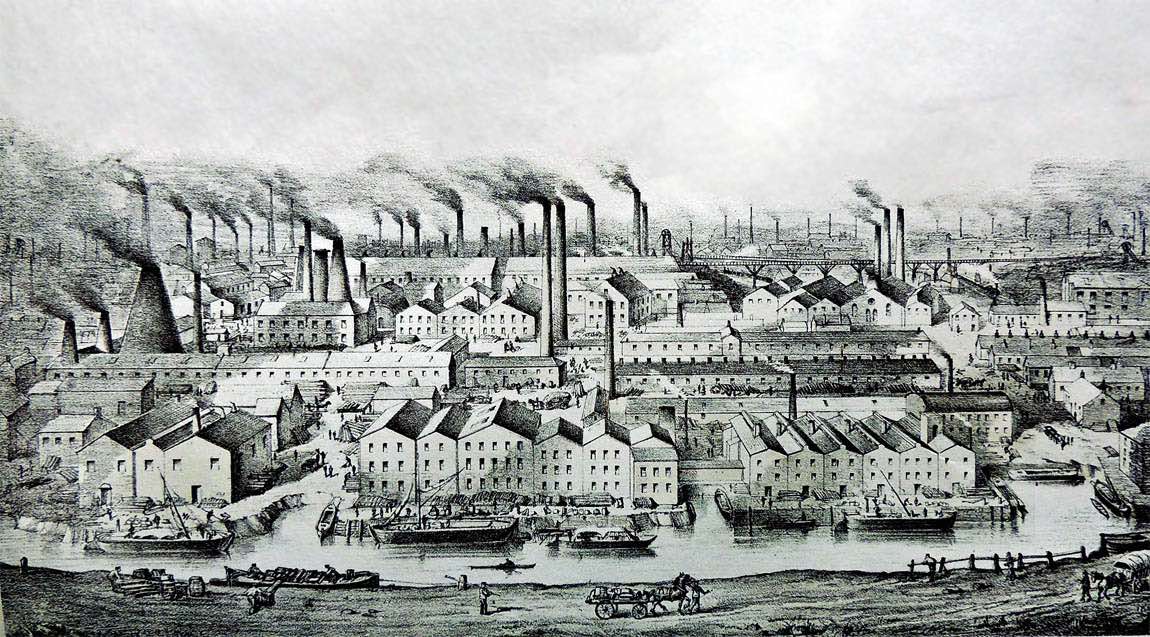

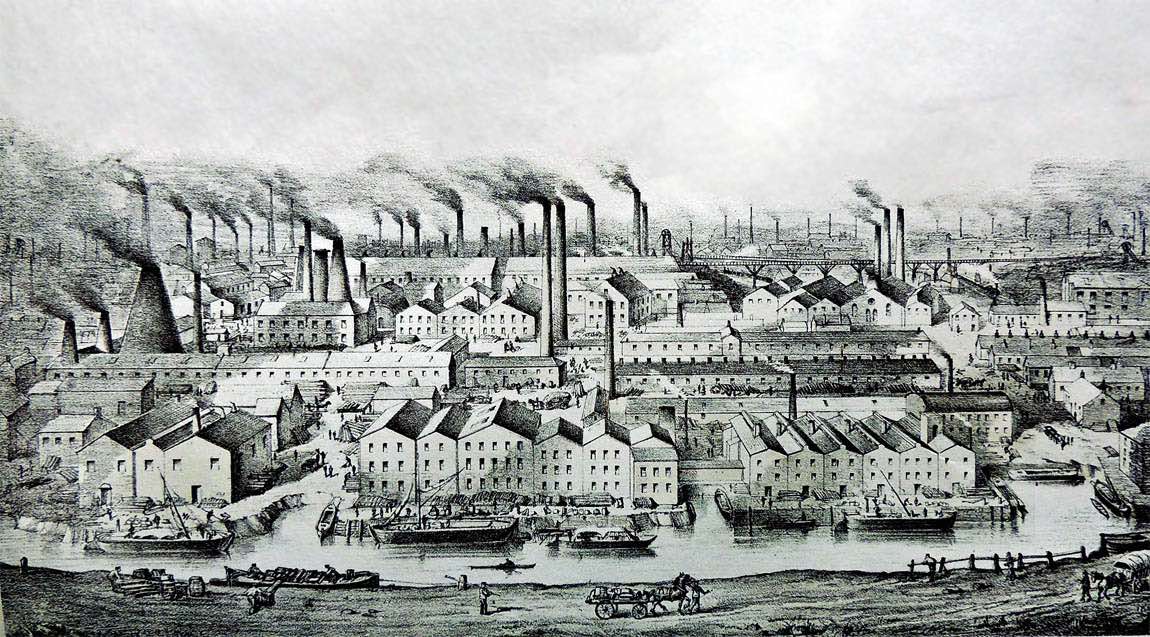

On the 24th the St Helens Newspaper published this piece about the ephemeral nature of life – especially for factory workers in the town: "There has been no lack of fatal misadventures in St. Helens of late, but none so dreadful as the boiler explosion which we report this week. Those who have to toil from day to day in our busy hives have sad experience of the uncertainty of human life, and the painful sacrifices which industry demands from those on whom the burden of it falls. The public have become so accustomed to fatal accidents that it is little wonder if those in the minor class give rise to but a moment's thought; but the catastrophe of Sunday last is one that from its very nature commands the deepest interest of all. "The loss of life is most deplorable, and the destruction of property to be regretted; they are sad but almost inevitable effects of such a cause as the bursting of every one boiler in the midst of a busy manufactory. But the accident reminds us that the residents of this borough are enclosed within a belt of boilers." In fact in 1870 it was reported that there were 345 large chimneys in St Helens (as depicted in the above illustration from 1879) all pumping out smoke from industrial furnaces and boilers.

"The loss of life is most deplorable, and the destruction of property to be regretted; they are sad but almost inevitable effects of such a cause as the bursting of every one boiler in the midst of a busy manufactory. But the accident reminds us that the residents of this borough are enclosed within a belt of boilers." In fact in 1870 it was reported that there were 345 large chimneys in St Helens (as depicted in the above illustration from 1879) all pumping out smoke from industrial furnaces and boilers.

And finally, this week's most interesting court case concerned an action that John Greener bravely brought in St Helens Petty Sessions. The apprentice at Pilkington's glassworks had summoned his foreman, John Henderson, for boxing his ears through taking too long to obtain an urgently needed plank. The St Helens Newspaper described the foreman's defence:

"He sent the complainant for a plank, and the lad made so much delay that he had to be reprimanded, as the metal was wasting. He muttered impertinently in return, and then got his ears boxed." Two other apprentices give evidence in support of John Greener's claim – but the foreman brought his own witnesses to support his view that the boy was slow and needed punishing. And so the magistrates dismissed the case and I expect the three apprentices did not have it easy from their boss after that!

Next week's stories will include the inquest hearing into the Pocket Nook boiler blast, the lazy vagabond who jumped from the frying pan into the fire, the toddler playing with matches in Mill Street and the stake out on a Liverpool Street beerhouse.

We begin with a meeting of the Crank Band of Hope during the evening of the 21st. The speaker was Rev. Miller from St Helens who gave a speech on the "power of evil habits" and expressed his hope that such temperance groups as Crank's would save thousands of young people "from the habits that now terribly enslaved so many of the old".

The Prescot Petty Sessions heard that a girl called Ann Giblin had stolen 6s 6d from the drawer of a beerhouse in Kemble Street in Prescot after ordering a pint of beer. The 10-year-old's father, John Giblin, said he could do no good with his child, having sent her to school – but instead she loitered about the streets. However, the 1871 census, taken 11 months earlier, has the girl listed as a labourer, along with her 12-year-old sister Mary. The siblings' younger brothers, though, are both marked as scholars.

If it had been the child’s first offence and there had been a suitable plea from the father, it is likely that the magistrates would have treated Ann more favourably. But once her Dad used the words "can do no good with him / her", long-term custody was the inevitable fate. So the girl from Bond Street in Prescot was sent to prison for a month and then onto a reformatory for five years.

This week's turns at the St Helens Theatre Royal Concert Hall were again centred on minstrel performances by black artists and the so-called serio-comics. Grotesque parodies of black life in America and dry humoured comedians were probably the two most popular forms of entertainment in the 1870s. The latter continues to this day with the Les Dawson / Jack Dee brand of comedy but thankfully the former in all its forms has long gone.

All but one of the five acts playing in the premises we know as the Citadel this week fitted into the serio-comic and black comic categories and were: Harry Dales ("The original “Lazy Sam”"); Miss Clara Robie ("Serio-comic and dancer"); Sam Redden ("Negro comedian"); Miss Julia Sutherland ("Excellent serio-comic, singer and dancer") and D’Osta and Little Ebor ("First-class gymnasts").

A review of Harry Dales' performance in London from June 1872 said: "Mr. Harry Dales supplies the “Ni**er” element. On the night of our visit he sang a somewhat dolorous [sad] medley concerning “Uncle Tom,” but we soon forgot this in his subsequent agility. Mr. Hales calls himself the original “Lazy Sam,” but his nimbleness of foot belies his title. A better performer on the bones we have never heard."

And an advert for Sam Redden in The Era trade newspaper in 1873 said: "The original and only Sam Redden, the Celebrated Negro Comedian, Stump Orator, Instrumentalist, Vocalist, and Eccentric Dancer, now on a successful tour through Wales, in his unique entertainment, entitled “Down South,” acknowledged by proprietors, public, and press to be the ne plus ultra of Negro Minstrelsy. “Causes screams of laughter without the slightest tinge of vulgarity”."

The St Helens Newspaper wrote on the 24th: "A conflagration of the most destructive character broke out at Eltonhead Farm, Sutton Heath, on Sunday night". It was another example of the difficulties incurred in the 1870s when a serious fire occurred in a rural area. No telephones to rapidly communicate news of the outbreak to a fire brigade and no motor vehicles or high quality roads to rapidly transport them to the blaze.

Then there was the issue of sourcing a water supply and efficiently playing it on the fire. No wonder the Newspaper wrote that it had been apparent from an early stage that the building was "doomed". The Lowe family ran Eltonhead Farm and a man who spotted the blaze in a large barn late at night dashed to the nearby home of Thomas Lowe to break the news. After releasing some cattle from the burning building, Lowe rode on horseback to Rainhill Lunatic Asylum – as it was then known.

Because of the time it took for town brigades to reach out of the way locations, some works and institutions kept their own engines. Rainhill asylum kept one and a small brigade of men. As they made their way to Eltonhead, Thomas Lowe rode on to Prescot to summon the town brigade. Once both units were in position, Dr Thomas Rogers took charge. The Newspaper credited his "energy and coolness" in localising the fire.

Dr Rogers was the superintendent in charge of Rainhill Asylum and clearly did a good job – although I think if my place was on fire, I would not expect a doctor in charge of a mental hospital to be commanding the fire brigade! The fire raged all night and an immense quantity of unthreshed wheat stored in the granary was destroyed and six heifers died. Then the fire began again in the afternoon. It was supposed that a labourer sleeping on the premises had caused it. The man had not been seen since and it was thought he might have been burned to death in the inferno.

However, that is not the end of this account. A letter was subsequently published in the Newspaper condemning the St Helens Borough Fire Brigade. It was claimed that they had been notified of the blaze both by telegram and special messenger (i.e. man on a horse) around midnight on the Sunday evening – but didn't show up until 4pm on the Monday afternoon! And then it was stated that they wanted a reassurance of their beer supply before setting to work. "“No beer no water” appeared to be the motto", claimed the correspondent.

The lengthy delay in the fire brigade’s arrival might have been connected with another emergency that had taken place ten hours earlier. The Sheffield Daily Telegraph described what had occurred: "On Sunday afternoon, at two o'clock, five boilers, filled with caustic soda, exploded at Messrs. Evans and McBryde's chemical works, Pocket Nook, near St. Helens, causing the loss of three lives and serious destruction of property.

"So great was the force of the explosion that half of one of the boilers was hurled a distance of 250 yards, and embedded several feet in the soil. Another great mass of iron was thrown on to the roof of glassworks, which it smashed in. The sheds under which the boilers stood were thrown into the air a great height, and were enveloped in a cloud of steam, which, with the terrific noise which accompanied the explosion, was seen and heard for miles round.

"Fortunately, it was Sunday, but few persons were at the works, except those engaged at the engine and boiler, and the loss of life has not been so great as the extent of the damage would lead one to suppose. A space of about 2,500 square yards, where the boilers and oxidisers stood, is a heap of ruins, and the roofs and windows in the neighbourhood have suffered considerably from the missiles which were thrown into the air by the explosion."

In fact four men were killed and eight injuried. The dead were William Marsh from Blackbrook; Michael Kelly of Greenbank; William Plumbley from Eccleston and James Lee. The St Helens Newspaper described the latter as "a black man of Pocket Nook" who lived in lodgings in David Street.

Several persons walking in the vicinity of the works were also badly scalded or otherwise hurt by boiling liquid falling upon them. Some were children playing in a field. The injured included a 7-year-old boy called Michael Gallagher ("badly scalded all over the body") and 9-year-old Francis Gallagher ("arm broken, large scalp wound, bruised"). Catherine Roberts of David Street in Pocket Nook was also severely scalded by the hot caustic landing on her while she'd been passing the works.

On the 24th the St Helens Newspaper published this piece about the ephemeral nature of life – especially for factory workers in the town: "There has been no lack of fatal misadventures in St. Helens of late, but none so dreadful as the boiler explosion which we report this week. Those who have to toil from day to day in our busy hives have sad experience of the uncertainty of human life, and the painful sacrifices which industry demands from those on whom the burden of it falls. The public have become so accustomed to fatal accidents that it is little wonder if those in the minor class give rise to but a moment's thought; but the catastrophe of Sunday last is one that from its very nature commands the deepest interest of all.

And finally, this week's most interesting court case concerned an action that John Greener bravely brought in St Helens Petty Sessions. The apprentice at Pilkington's glassworks had summoned his foreman, John Henderson, for boxing his ears through taking too long to obtain an urgently needed plank. The St Helens Newspaper described the foreman's defence:

"He sent the complainant for a plank, and the lad made so much delay that he had to be reprimanded, as the metal was wasting. He muttered impertinently in return, and then got his ears boxed." Two other apprentices give evidence in support of John Greener's claim – but the foreman brought his own witnesses to support his view that the boy was slow and needed punishing. And so the magistrates dismissed the case and I expect the three apprentices did not have it easy from their boss after that!

Next week's stories will include the inquest hearing into the Pocket Nook boiler blast, the lazy vagabond who jumped from the frying pan into the fire, the toddler playing with matches in Mill Street and the stake out on a Liverpool Street beerhouse.

This week's stories include the deadly boiler explosion in a St Helens chemical works, the fire that raged all night in Sutton Heath, the black artists and serio-comics at the Theatre Royal, the 10-year-old Prescot girl who was sent to prison and the Pilkington apprentice who prosecuted his foreman for boxing his ears.

We begin with a meeting of the Crank Band of Hope during the evening of the 21st.

The speaker was Rev. Miller from St Helens who gave a speech on the "power of evil habits" and expressed his hope that such temperance groups as Crank's would save thousands of young people "from the habits that now terribly enslaved so many of the old".

The Prescot Petty Sessions heard that a girl called Ann Giblin had stolen 6s 6d from the drawer of a beerhouse in Kemble Street in Prescot after ordering a pint of beer.

The 10-year-old's father, John Giblin, said he could do no good with his child, having sent her to school – but instead she loitered about the streets.

However, the 1871 census, taken 11 months earlier, has the girl listed as a labourer, along with her 12-year-old sister Mary. The siblings' younger brothers, though, are both marked as scholars.

If it had been the child’s first offence and there had been a suitable plea from the father, it is likely that the magistrates would have treated Ann more favourably.

But once her Dad used the words "can do no good with him / her", long-term custody was the inevitable fate.

So the girl from Bond Street in Prescot was sent to prison for a month and then onto a reformatory for five years.

This week's turns at the St Helens Theatre Royal Concert Hall were again centred on minstrel performances by black artists and the so-called serio-comics.

Grotesque parodies of black life in America and dry humoured comedians were probably the two most popular forms of entertainment in the 1870s.

The latter continues to this day with the Les Dawson / Jack Dee brand of comedy but thankfully the former in all its forms has long gone.

All but one of the five acts playing in the premises we know as the Citadel this week fitted into the serio-comic and black comic categories and were:

Harry Dales ("The original “Lazy Sam”"); Miss Clara Robie ("Serio-comic and dancer"); Sam Redden ("Negro comedian"); Miss Julia Sutherland ("Excellent serio-comic, singer and dancer") and D’Osta and Little Ebor ("First-class gymnasts").

A review of Harry Dales' performance in London from June 1872 said:

"Mr. Harry Dales supplies the “Ni**er” element. On the night of our visit he sang a somewhat dolorous [sad] medley concerning “Uncle Tom,” but we soon forgot this in his subsequent agility. Mr. Hales calls himself the original “Lazy Sam,” but his nimbleness of foot belies his title. A better performer on the bones we have never heard."

And an advert for Sam Redden in The Era trade newspaper in 1873 said:

"The original and only Sam Redden, the Celebrated Negro Comedian, Stump Orator, Instrumentalist, Vocalist, and Eccentric Dancer, now on a successful tour through Wales, in his unique entertainment, entitled “Down South,” acknowledged by proprietors, public, and press to be the ne plus ultra of Negro Minstrelsy. “Causes screams of laughter without the slightest tinge of vulgarity”."

The St Helens Newspaper wrote on the 24th: "A conflagration of the most destructive character broke out at Eltonhead Farm, Sutton Heath, on Sunday night".

It was another example of the difficulties incurred in the 1870s when a serious fire occurred in a rural area.

No telephones to rapidly communicate news of the outbreak to a fire brigade and no motor vehicles or high quality roads to rapidly transport them to the blaze.

Then there was the issue of sourcing a water supply and efficiently playing it on the fire.

No wonder the Newspaper wrote that it had been apparent from an early stage that the building was "doomed".

The Lowe family ran Eltonhead Farm and a man who spotted the blaze in a large barn late at night dashed to the nearby home of Thomas Lowe to break the news.

After releasing some cattle from the burning building, Lowe rode on horseback to Rainhill Lunatic Asylum – as it was then known.

Because of the time it took for town brigades to reach out of the way locations, some works and institutions kept their own engines.

Rainhill asylum kept one and a small brigade of men. As they made their way to Eltonhead, Thomas Lowe rode on to Prescot to summon the town brigade.

Once both units were in position, Dr Thomas Rogers took charge. The Newspaper credited his "energy and coolness" in localising the fire.

Dr Rogers was the superintendent in charge of Rainhill Asylum and clearly did a good job – although I think if my place was on fire, I would not expect a doctor in charge of a mental hospital to be commanding the fire brigade!

The fire raged all night and an immense quantity of unthreshed wheat stored in the granary was destroyed and six heifers died. Then the fire began again in the afternoon.

It was supposed that a labourer sleeping on the premises had caused it. The man had not been seen since and it was thought he might have been burned to death in the inferno.

However, that is not the end of this account. A letter was subsequently published in the Newspaper condemning the St Helens Borough Fire Brigade.

It was claimed that they had been notified of the blaze both by telegram and special messenger (i.e. man on a horse) around midnight on the Sunday evening – but didn't show up until 4pm on the Monday afternoon!

And then it was stated that they wanted a reassurance of their beer supply before setting to work. "“No beer no water” appeared to be the motto", claimed the correspondent.

The lengthy delay in the fire brigade’s arrival might have been connected with another emergency that had taken place ten hours earlier. The Sheffield Daily Telegraph described what had occurred:

"On Sunday afternoon, at two o'clock, five boilers, filled with caustic soda, exploded at Messrs. Evans and McBryde's chemical works, Pocket Nook, near St. Helens, causing the loss of three lives and serious destruction of property.

"So great was the force of the explosion that half of one of the boilers was hurled a distance of 250 yards, and embedded several feet in the soil. Another great mass of iron was thrown on to the roof of glassworks, which it smashed in.

"The sheds under which the boilers stood were thrown into the air a great height, and were enveloped in a cloud of steam, which, with the terrific noise which accompanied the explosion, was seen and heard for miles round.

"Fortunately, it was Sunday, but few persons were at the works, except those engaged at the engine and boiler, and the loss of life has not been so great as the extent of the damage would lead one to suppose.

"A space of about 2,500 square yards, where the boilers and oxidisers stood, is a heap of ruins, and the roofs and windows in the neighbourhood have suffered considerably from the missiles which were thrown into the air by the explosion."

In fact four men were killed and eight injuried. The dead were William Marsh from Blackbrook; Michael Kelly of Greenbank; William Plumbley from Eccleston and James Lee.

The St Helens Newspaper described the latter as "a black man of Pocket Nook" who lived in lodgings in David Street.

Several persons walking in the vicinity of the works were also badly scalded or otherwise hurt by boiling liquid falling upon them. Some were children playing in a field.

The injured included a 7-year-old boy called Michael Gallagher ("badly scalded all over the body") and 9-year-old Francis Gallagher ("arm broken, large scalp wound, bruised").

Catherine Roberts of David Street in Pocket Nook was also severely scalded by the hot caustic landing on her while she'd been passing the works.

On the 24th the St Helens Newspaper published this piece about the ephemeral nature of life – especially for factory workers in the town:

"There has been no lack of fatal misadventures in St. Helens of late, but none so dreadful as the boiler explosion which we report this week.

"Those who have to toil from day to day in our busy hives have sad experience of the uncertainty of human life, and the painful sacrifices which industry demands from those on whom the burden of it falls.

"The public have become so accustomed to fatal accidents that it is little wonder if those in the minor class give rise to but a moment's thought; but the catastrophe of Sunday last is one that from its very nature commands the deepest interest of all.

"The loss of life is most deplorable, and the destruction of property to be regretted; they are sad but almost inevitable effects of such a cause as the bursting of every one boiler in the midst of a busy manufactory.

"But the accident reminds us that the residents of this borough are enclosed within a belt of boilers." In fact in 1870 it was reported that there were 345 large chimneys in St Helens (as depicted in the above illustration from 1879) all pumping out smoke from industrial furnaces and boilers.

In fact in 1870 it was reported that there were 345 large chimneys in St Helens (as depicted in the above illustration from 1879) all pumping out smoke from industrial furnaces and boilers.

And finally, this week's most interesting court case concerned an action that John Greener bravely brought in St Helens Petty Sessions.

The apprentice at Pilkington's glassworks had summoned his foreman, John Henderson, for boxing his ears through taking too long to obtain an urgently needed plank. The St Helens Newspaper described the foreman's defence:

"He sent the complainant for a plank, and the lad made so much delay that he had to be reprimanded, as the metal was wasting. He muttered impertinently in return, and then got his ears boxed."

Two other apprentices give evidence in support of John Greener's claim – but the foreman brought his own witnesses to support his view that the boy was slow and needed punishing.

And so the magistrates dismissed the case and I expect the three apprentices did not have it easy from their boss after that!

Next week's stories will include the inquest hearing into the Pocket Nook boiler blast, the lazy vagabond who jumped from the frying pan into the fire, the toddler playing with matches in Mill Street and the stake out on a Liverpool Street beerhouse.

We begin with a meeting of the Crank Band of Hope during the evening of the 21st.

The speaker was Rev. Miller from St Helens who gave a speech on the "power of evil habits" and expressed his hope that such temperance groups as Crank's would save thousands of young people "from the habits that now terribly enslaved so many of the old".

The Prescot Petty Sessions heard that a girl called Ann Giblin had stolen 6s 6d from the drawer of a beerhouse in Kemble Street in Prescot after ordering a pint of beer.

The 10-year-old's father, John Giblin, said he could do no good with his child, having sent her to school – but instead she loitered about the streets.

However, the 1871 census, taken 11 months earlier, has the girl listed as a labourer, along with her 12-year-old sister Mary. The siblings' younger brothers, though, are both marked as scholars.

If it had been the child’s first offence and there had been a suitable plea from the father, it is likely that the magistrates would have treated Ann more favourably.

But once her Dad used the words "can do no good with him / her", long-term custody was the inevitable fate.

So the girl from Bond Street in Prescot was sent to prison for a month and then onto a reformatory for five years.

This week's turns at the St Helens Theatre Royal Concert Hall were again centred on minstrel performances by black artists and the so-called serio-comics.

Grotesque parodies of black life in America and dry humoured comedians were probably the two most popular forms of entertainment in the 1870s.

The latter continues to this day with the Les Dawson / Jack Dee brand of comedy but thankfully the former in all its forms has long gone.

All but one of the five acts playing in the premises we know as the Citadel this week fitted into the serio-comic and black comic categories and were:

Harry Dales ("The original “Lazy Sam”"); Miss Clara Robie ("Serio-comic and dancer"); Sam Redden ("Negro comedian"); Miss Julia Sutherland ("Excellent serio-comic, singer and dancer") and D’Osta and Little Ebor ("First-class gymnasts").

A review of Harry Dales' performance in London from June 1872 said:

"Mr. Harry Dales supplies the “Ni**er” element. On the night of our visit he sang a somewhat dolorous [sad] medley concerning “Uncle Tom,” but we soon forgot this in his subsequent agility. Mr. Hales calls himself the original “Lazy Sam,” but his nimbleness of foot belies his title. A better performer on the bones we have never heard."

And an advert for Sam Redden in The Era trade newspaper in 1873 said:

"The original and only Sam Redden, the Celebrated Negro Comedian, Stump Orator, Instrumentalist, Vocalist, and Eccentric Dancer, now on a successful tour through Wales, in his unique entertainment, entitled “Down South,” acknowledged by proprietors, public, and press to be the ne plus ultra of Negro Minstrelsy. “Causes screams of laughter without the slightest tinge of vulgarity”."

The St Helens Newspaper wrote on the 24th: "A conflagration of the most destructive character broke out at Eltonhead Farm, Sutton Heath, on Sunday night".

It was another example of the difficulties incurred in the 1870s when a serious fire occurred in a rural area.

No telephones to rapidly communicate news of the outbreak to a fire brigade and no motor vehicles or high quality roads to rapidly transport them to the blaze.

Then there was the issue of sourcing a water supply and efficiently playing it on the fire.

No wonder the Newspaper wrote that it had been apparent from an early stage that the building was "doomed".

The Lowe family ran Eltonhead Farm and a man who spotted the blaze in a large barn late at night dashed to the nearby home of Thomas Lowe to break the news.

After releasing some cattle from the burning building, Lowe rode on horseback to Rainhill Lunatic Asylum – as it was then known.

Because of the time it took for town brigades to reach out of the way locations, some works and institutions kept their own engines.

Rainhill asylum kept one and a small brigade of men. As they made their way to Eltonhead, Thomas Lowe rode on to Prescot to summon the town brigade.

Once both units were in position, Dr Thomas Rogers took charge. The Newspaper credited his "energy and coolness" in localising the fire.

Dr Rogers was the superintendent in charge of Rainhill Asylum and clearly did a good job – although I think if my place was on fire, I would not expect a doctor in charge of a mental hospital to be commanding the fire brigade!

The fire raged all night and an immense quantity of unthreshed wheat stored in the granary was destroyed and six heifers died. Then the fire began again in the afternoon.

It was supposed that a labourer sleeping on the premises had caused it. The man had not been seen since and it was thought he might have been burned to death in the inferno.

However, that is not the end of this account. A letter was subsequently published in the Newspaper condemning the St Helens Borough Fire Brigade.

It was claimed that they had been notified of the blaze both by telegram and special messenger (i.e. man on a horse) around midnight on the Sunday evening – but didn't show up until 4pm on the Monday afternoon!

And then it was stated that they wanted a reassurance of their beer supply before setting to work. "“No beer no water” appeared to be the motto", claimed the correspondent.

The lengthy delay in the fire brigade’s arrival might have been connected with another emergency that had taken place ten hours earlier. The Sheffield Daily Telegraph described what had occurred:

"On Sunday afternoon, at two o'clock, five boilers, filled with caustic soda, exploded at Messrs. Evans and McBryde's chemical works, Pocket Nook, near St. Helens, causing the loss of three lives and serious destruction of property.

"So great was the force of the explosion that half of one of the boilers was hurled a distance of 250 yards, and embedded several feet in the soil. Another great mass of iron was thrown on to the roof of glassworks, which it smashed in.

"The sheds under which the boilers stood were thrown into the air a great height, and were enveloped in a cloud of steam, which, with the terrific noise which accompanied the explosion, was seen and heard for miles round.

"Fortunately, it was Sunday, but few persons were at the works, except those engaged at the engine and boiler, and the loss of life has not been so great as the extent of the damage would lead one to suppose.

"A space of about 2,500 square yards, where the boilers and oxidisers stood, is a heap of ruins, and the roofs and windows in the neighbourhood have suffered considerably from the missiles which were thrown into the air by the explosion."

In fact four men were killed and eight injuried. The dead were William Marsh from Blackbrook; Michael Kelly of Greenbank; William Plumbley from Eccleston and James Lee.

The St Helens Newspaper described the latter as "a black man of Pocket Nook" who lived in lodgings in David Street.

Several persons walking in the vicinity of the works were also badly scalded or otherwise hurt by boiling liquid falling upon them. Some were children playing in a field.

The injured included a 7-year-old boy called Michael Gallagher ("badly scalded all over the body") and 9-year-old Francis Gallagher ("arm broken, large scalp wound, bruised").

Catherine Roberts of David Street in Pocket Nook was also severely scalded by the hot caustic landing on her while she'd been passing the works.

On the 24th the St Helens Newspaper published this piece about the ephemeral nature of life – especially for factory workers in the town:

"There has been no lack of fatal misadventures in St. Helens of late, but none so dreadful as the boiler explosion which we report this week.

"Those who have to toil from day to day in our busy hives have sad experience of the uncertainty of human life, and the painful sacrifices which industry demands from those on whom the burden of it falls.

"The public have become so accustomed to fatal accidents that it is little wonder if those in the minor class give rise to but a moment's thought; but the catastrophe of Sunday last is one that from its very nature commands the deepest interest of all.

"The loss of life is most deplorable, and the destruction of property to be regretted; they are sad but almost inevitable effects of such a cause as the bursting of every one boiler in the midst of a busy manufactory.

"But the accident reminds us that the residents of this borough are enclosed within a belt of boilers."

And finally, this week's most interesting court case concerned an action that John Greener bravely brought in St Helens Petty Sessions.

The apprentice at Pilkington's glassworks had summoned his foreman, John Henderson, for boxing his ears through taking too long to obtain an urgently needed plank. The St Helens Newspaper described the foreman's defence:

"He sent the complainant for a plank, and the lad made so much delay that he had to be reprimanded, as the metal was wasting. He muttered impertinently in return, and then got his ears boxed."

Two other apprentices give evidence in support of John Greener's claim – but the foreman brought his own witnesses to support his view that the boy was slow and needed punishing.

And so the magistrates dismissed the case and I expect the three apprentices did not have it easy from their boss after that!

Next week's stories will include the inquest hearing into the Pocket Nook boiler blast, the lazy vagabond who jumped from the frying pan into the fire, the toddler playing with matches in Mill Street and the stake out on a Liverpool Street beerhouse.